Introduction

Print disabled means: "A person who cannot effectively read print because of a visual, physical, perceptual, developmental, cognitive, or learning disability." [1]

This chapter focuses on how assistive technology can help print disabled people. The term was coined when printed materials dominated our information society. Today, digital publications can empower people who otherwise cannot read. Unfortunately, if poorly designed, they present many of the same barriers as materials printed on paper.

Reading is not limited to something people do with their eyes. People with print disabilities read with their eyes, ears, fingers, and combinations of them. Reading means gaining an effective understanding of the content. A blind person who listens to words is reading, just as is one reading Braille.

The concept of effective reading is significant. Low-vision students using magnifying glasses to read two pages an hour are not reading effectively, although they understand the information. Likewise, dyslexic students who need most of their mental capacity to decode words, but who cannot comprehend their meaning, are not reading effectively. Effective reading means reading at a normal speed with normal comprehension.

We always consider the person before the disability. The People First movement recommended putting the person before the disability, i.e., a person who is blind, rather than a blind person. This convention has been relaxed recently. The National Federation of the Blind (NFB) and the American Council of the Blind (ACB) both use the term “the blind” to describe themselves. In this module, we will use both ways of describing persons with disabilities, but we will always consider the person ahead of the disability.

Summary

We have learned what a print disability is, and that people read with their eyes, ears, and fingers. We know disabilities interfere with reading printed materials and text on screens. Finally, we understand that our focus is on effective reading.

Types of Disabilities that Affect Reading

Before we address specific disabilities, we need to understand the wide range of difficulty reading that people have within each disability group. We could use the word “spectrum” for this range, but “spectrum” is associated specifically with autism.

Legal Blindness, sometimes called statutory blindness, is a technical term that means a person’s vision meets the legal definition of blindness. However, many people with low vision do not meet the legal definition of being blind but cannot read print effectively. Here is a perfect example of the wide range of visual impairments, from people who are totally blind to people who have low vision and who need help to read effectively.

The latest copyright exception legislation no longer requires people with visual impairments to be legally blind to qualify for services for blind people. The rule now reflects the understanding that if there is any visual impairment that prevents someone from reading effectively, they qualify under the amendment. See the Chapter 8 on Libraries Serving People with Disabilities for more information on copyright and qualifying for services to the blind.

“Learning differences” affect a large group of individuals who process information differently than most people do. “Learning differences” has replaced an older term, “learning disabilities”, which has fallen out of favor. People who have dyslexia make up much of this group, but there are other disabilities that include learning differences. This group is huge. As cited in the Introduction, studies done at Yale and Cornell put the number at 20% of the population and show that 80-90% of this group has dyslexia.

Dyslexia has a major impact on reading. Brain scans can identify physical differences in the pathways that process symbolic information. The Dyslexic Advantage movement has identified many gifted people who are dyslexic, including Dr. Temple Grandin, Richard Branson, Whoopi Goldberg, and Charles Schwab.

While K-12 schools are getting better at serving students with learning differences, many adults went through school before this became common, and they were traumatized. It is estimated that 50% of people who are incarcerated are dyslexic. Trouble reading makes success in school and society difficult.

Dyslexia ranges from mild to severe. Some people can learn to minimize it, but others can never read effectively without assistive technology. We can do a lot in our libraries to help them.

Most people with learning differences do not use the term “disability” to describe themselves. Some may say they are dyslexic, but not say they have a disability. This is like older adults who are experiencing vision loss. They may say they cannot see well, but do not describe themselves as blind or disabled.

This group includes people who have undergone amputation or had a stroke, or have cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, arthritis, or spinal cord injury. Other conditions may cause problems holding a book or turning pages.

There are mechanical devices to hold books and turn pages for them, but fortunately, the digital revolution has made it significantly easier for people who cannot manipulate print materials to read digital versions.

People in this category may also have learning differences and visual problems, but the critical issue in using a computer is finding alternatives to the keyboard, mouse, and gestures. Assistive technologies such as sticky keys, Eye Gaze, single switches, and speech recognition are some alternatives.

There is a vast range in the severity of disabilities within the print-disabled population. Learning differences, including dyslexia, account for 80-90% of this population. The overall print-disabled population includes over 20% of the US population. Many of these people do not use the word disabled to describe themselves. Because of bad experiences in school and a lack of access to assistive technology, many of them do not enjoy reading. As librarians, we can bring them assistive technology to make reading fun and give them a wonderful lifelong activity, as well as access to educational and employment benefits opportunities.

Assistive Technology (AT) for Computers, Tablets, and Smart Phones

This section will focus on AT for reading digital books, web pages, etc., on digital devices. The next section is about AT for reading printed materials.

Screen readers read the text on the screen aloud. They also work with an enlarged character display or refreshable Braille.

Regardless of the devices they are used on, they all have similar functionality:

- They can load on startup. This is the normal configuration for a personal system. It allows access to the login screen, and then loads the screen reader as the device completes the boot-up process, so it is the most convenient.

- In a shared computer environment, such as a school or library where people share computers, the screen reader can be launched with a shortcut key, by clicking on an icon, or by speaking a command.

- Screen readers use the device’s built-in Text-To-Speech (TTS) or TTS that comes with the screen reader.

- TTS speaking rate, tone, pitch, and speaking voice can be adjusted to suit personal preferences.

- In shared environments like schools or libraries, profiles of these preferences can be saved, so each user has to set them only once.

- Screen readers should enable access to all functions of the operating system, though some do not.

- Screen readers are sophisticated and require training because apps are created for visual use. Using a screen reader adds a layer of complexity. Users control screen readers with the keyboard or an additional layer of gestures.

- Screen readers work only with compatible apps.

Compatible means an app works well with screen readers. Many do. However, some do not work at all, and some have significant shortcomings. In addition, some apps work for low vision users but not for totally blind people. Later in this module, you will learn how to select the right apps for individual patrons.

The first screen readers were developed for MS-DOS and then Windows. Consequently, most blind people use Windows rather than Mac. Although the community of Mac users is growing, it is still small compared to blind people who use Windows. Younger people often prefer smart phones and tablets. These provide an excellent experience for reading digital books. However, only personal computers support the more powerful reading systems, which are necessary for success at school and work.

Job Access with Speech (JAWS) for Windows from Freedom Scientific is one of the oldest and best known screen readers. Blind people have used it for many decades, so it has a large user base. Freedom Scientific offers extensive training and technical support, and the user community offers additional help. It is costly compared to its alternatives. The base license is approximately $1,000 and there are also maintenance fees. The home edition for individuals is $95 per year. It does not come as part of Windows, so it must be installed on the computer.

Non-Visual Desktop Access (NVDA) for Windows from Non-Visual Access is open source and free, with donations requested. NVDA is a sophisticated screen reader that rivals the functionality of JAWS. It has a large user base worldwide and excellent documentation. The user base is active on discussion lists and provides support. Paid technical support is also available. NVDA must be installed. It does not come as part of Windows.

Narrator for Windows by Microsoft is the built-in screen reader that comes on all Windows computers. Microsoft has vastly improved this screen reader, and it rivals JAWS and NVDA.

VoiceOver for Mac from Apple is the built-in Mac screen reader. It is sophisticated and full-featured.

VoiceOver for iPhone and iPad from Apple is built in to the iPhone and iPad. It is very sophisticated, popular, and optimized for gestures on touchscreen devices. It is also compatible with Bluetooth keyboards.

TalkBack for Android from Google comes with all Android tablets, smart phones, and other devices. It is very sophisticated. TalkBack may behave differently from one Android device to another because of differences in the TalkBack version, Android OS version, and hardware differences.

Video Demo

If you have ever been in an elevator or hotel, you have seen Braille and tactile graphics. The ADA requires elevator buttons and signage on hotel rooms to have both Braille and tactile (raised) numbers. Also, as you exit an elevator, there is a raised number showing the floor.

People who learn Braille at an early age grow up loving it. These fluent Braille readers can read fast (over 300 words a minute) and view Braille as their primary method of reading. Some people who learn Braille as adults also become fluent in it. Estimates show that only 8% of the blind population are Braille readers. However, it is important for librarians to support access to Braille content for them.

In the pre-digital age, Braille was made with raised dots on paper pages. The dots were organized into cells. Each cell represented a character. This is called embossed Braille. Most Braille readers learned to read with it. Refreshable Braille uses the same dot system, but delivers it on an electronic device that raises and lowers the dots so one device can deliver an infinite number of pages and books. This is analogous to the difference between a printed book and a smart phone. A printed book is one book. Same for embossed Braille. But a smart phone can deliver many books, and so can a refreshable Braille display. Increasingly, Braille readers are turning to refreshable displays and away from embossed paper.

Refreshable devices normally interface with a PC, Mac, smart phone, or tablet through a Bluetooth connection. They are driven by the screen reader, which translates the text to Braille and sends it to the device. The screen reader can send text to the TTS engine for speaking and to the refreshable device for tactile use at the same time. This way, the person reading can listen to spoken words, read Braille, or both. This is a popular method for reading. The apps are the same ones described above. Most refreshable Braille displays show 20 to 40 characters (Braille cells). In recent years, refreshable Braille displays with multiple lines have been developed. These devices may someday also display tactile graphics. They are just entering the market and are a technology to watch.

In the past, refreshable Braille devices were expensive, costing thousands of dollars. Today, the prices are dropping below the $1,000 threshold, making them more affordable for blind people. The National Service for the Blind and Print Disabled (NLS) now distributes one that is free to anyone who qualifies for NLS services. This device has no TTS capabilities. It simply presents Braille.

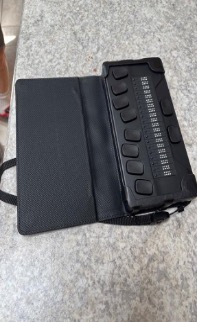

Personal notetakers form another class of refreshable Braille devices. These support applications, such as word processers, email, web browsers, and reading systems. They can also be used to read digital books. As always, the digital file must be compatible with the reading system. Here is what one looks like:

All computer, smart phone, and tablet operating systems offer built-in screen magnification, color selection, contrast adjustment, and font selection. For persons with disabilities, these are essential. Here they are, one at a time:

- Magnification is critical for the low vision user, but it must be optimized for each person’s vision, and there is a point of diminishing returns because each increase in magnification means fewer words can fit onto the screen. Setting the magnification to twice the default size is 2x magnification and significantly reduces the number of words on the screen, so the person has to scroll or page-down more. Using screen magnification can also make finding one’s way around in text difficult, and the higher the magnification, the harder navigation becomes. A good solution for many people is to use TTS in combination with a screen reader. They listen to the TTS and use their vision only when trying to understand difficult passages. People with deteriorating vision have to increase magnification as their vision changes. Eventually, the magnification may become so hard to use that they decide to use only the screen reader. It is human nature to use vision for as long as possible, and some people keep trying beyond the point when the screen reader becomes their best option. Each operating system (OS) has its own way of adjusting magnification. One common approach is a virtual magnifying glass that can be moved around the screen. It magnifies the text and graphics under it. Another common approach is to enlarge everything on the screen and drag only part of it into view.

- Colors adjustments are important for low vision users and people with learning differences. Some foreground and background combinations work better than others, depending on the disability.

- Contrast, along with brightness, is also adjustable to prevent eye fatigue and make differentiating between text and background possible.

- Font selection is important for low vision users and persons with learning differences, including dyslexia. Serif fonts are problematic because the line thickness varies within each letter. A nine may look like a zero, with the downward portion of the nine tapering off at the end. A sans-serif font with an even line thickness is usually the most readable. Dyslexic friendly fonts are now available for operating and reading systems. Though there has been little research showing that these fonts work better than standard fonts, many people find them helpful. Some people with dyslexia use a single font for all reading. They sight read and learn how each word looks in that font. As long as they read only in that font, each word always looks the same. If they read in other fonts, the words look different, and they do not recognize them. We heard from an educational professional with dyslexia that when she reads in the font she knows, she has no disability and can read normally. Change the font, and she cannot read, and her disability is back.

Once the operating system has been personalized, many applications will inherit its settings. However, this is not always true, so settings in applications may need adjustment. Also, some reading systems for digital books have their own ways of adjusting the presentation that are better than the operating system’s. Adjustment of the font and other visual elements varies from book to book. They depend on how the book was formatted and can be affected if the file is locked. We will go into more detail when we explore file formats and specific reading systems.

Librarians are not responsible for helping people select or learn keyboard and mouse alternatives. Occupational therapists and other medical professionals set these up for their patients, but librarians still need to know about the equipment their patrons employ.

Computer operating systems now include a growing number of features so people with limited use of their hands can use them. Sticky keys and speech recognition are two of the most important.

“Sticky keys” was the first such feature. People who cannot hold down multiple keys at once use it. For example, one-handed people, or people who use mouth sticks to type. The person presses a sequence of keys and the computer interprets these presses as if they were simultaneous instead of sequential. This makes key combinations possible.

Speech recognition provides dictation and voice control over devices. It is built into apps such as Siri, Google Assistant, and Cortana.

Additional hardware and software can go far beyond what operating systems provide. For instance, single switch devices, such as sip-and-puff switches, combine with software so people without use of their hands can operate the equivalent of a computer mouse. The mouse can then operate a virtual keyboard and, through it, other apps. Gaze control technology goes even farther by allowing users to operate a computer by moving only their eyes. Eyegaze is an example of this.

Once someone has a workable solution, they can use it with the reading system and other apps.

Screen readers can be overkill for many people with learning differences. They only need an app to read aloud, or they use the OS TTS. For instance, in email, the subject lines and sender’s names are brief enough for them to read visually. They need only the body of the message read aloud.

Good solutions for them are Speak Screen and Speak Selected Text, both available through the OS accessibility settings on smart phones and tablets. Microsoft products, such as Word, also have immersive reading functions that provide high-powered reading options with TTS. Some other useful applications are:

- Text Help, a paid application that integrates into browsers. It also has an EPUB reader, to be discussed later.

- Kurzweil, a paid application famous for reading PDF documents aloud and doing Optical Character Recognition (OCR). It is described in more detail below.

- Natural Reader is a newer application that offers many appealing TTS uses.

This section covered high-level information about kinds of AT used on computers, tablets, and smart phones. Because so many options are available, finding the best combination for each person requires trial-and-error experimentation.

Traditional Assistive Technology in Libraries

Many libraries, especially on college campuses, have rooms dedicated to AT for disabled students to access printed books. The primary technologies are Closed Circuit TV (CCTV) for magnification, and flatbed scanners with OCR software for reading printed text aloud.

CCTV has been available for decades and is a popular low-vision aide. It is simply a TV with a camera mounted under it. Books and other documents go on a tray below the camera. The user moves them so the lens sees the part the user wants to read. There are adjustments for focus, color selection, and magnification. One well-known brand is Optelec. Many libraries make CCTV available to their patrons for use with books and documents brought in from outside the library collection, as well as with books from the library’s collection. CCTV is also useful for filling out forms.

Smart phones and tablets have similar technology built into their operating systems. Their utilities include a magnifier app. The screen displays what the rear-facing camera sees, such as a page of a book, and the app provides control over magnification, brightness, contrast, color filtering, and locking the focus. A phone can also be used to view objects around the user, like a pocket-sized telescope and microscope in one. If your library already has a CCTV, ask your patrons who use it if they have a smart phone or tablet and if they know about the magnifier available on the phone. The discovery of this app could be life-changing.

In 1976, Ray Kurzweil released the Kurzweil Reading Machine at a selling price $12,800. It was not intended for personal purchase. Libraries bought it for student and public use. Based on then-new optical character recognition (OCR) technology, it could read aloud anything printed in any font. Many libraries still have a dedicated room equipped with a Kurzweil machine, or a flat-bed scanner connected to a computer loaded with similar OCR software, such as ABBYY (pronounced Abby) Fine Reader, or Omni Page. Patrons scan pages and the OCR system reads them aloud. The Kurzweil Reading Machine was a leap forward from systems that could read only a few fonts, but that was 1976. Today, most of us have similar functionality built into our smart phones. Some readers still prefer Kurzweil and other systems over using their phones, but for many people, the phone is the best choice.

Manually scanning a print book one page at a time is time-consuming, even with a sophisticated system, such as the Kurzweil. This was once what college students had to do. Today, the college or university Disability Services Office (DSO) provides this service. The DSO chops off the binding and runs the pages through a double-sided sheet-fed scanner, and then through OCR software. Unfortunately, OCR software cannot interpret highly formatted materials, such as textbooks, accurately. To provide quality digital versions of textbooks, scanning errors must be corrected manually. Images also require manually adding alt text and extended descriptions.

Again, the smart phone has many of the same capabilities. Seeing AI, a free App from Microsoft, has OCR built in and works on iPhones and iPads. Google has a similar app for Android devices. With them, the camera can be used to OCR everything from business cards to full-page documents, and the app reads the content to the user. The apps described above in the Spoken Text section are also good options.

Much of this traditional technology is still used in libraries. However, the newer smart phone technology is more powerful, and can be life-changing for people to whom you introduce it.

Chapter Summary

You now have a high-level view of the varieties of Assistive Technology. You know there is a wide range of severity of disabilities and that people read with their ears and fingers as well as their eyes. Modern technology provides amazing breakthroughs for them to access information, and you can introduce them to it.